Jonathan Edwards and the “Christian Nation”

The region of the United States known as New England is indelibly stamped with the vestiges of Puritanism—just look, for example, at street names in New Haven (Walley, Goffe, Dixwell, Winthrop, Pierpont, etc.), or the names of surrounding towns (Hamden, Cromwell, Orange, etc.) and you will quickly get an idea of old sympathies. Puritanism was an English religious, moral, and ecclesiastical reform movement that began in the 16th century, reached its apex in the revolution and Protectorate of the mid-17th century, and culminated with the restoration of the monarchy in 1660.

Edwards perpetuated what Native historian Ned Blackhawk calls “the presumption of the sanctity of spiritual colonization,” in which Europeans equated their exploitation and oppression of Natives and Africans with the will of God.

And yet, in other ways it endured, particularly as a religious persuasion, known as Dissent, with distinct theological, devotional, ideological, and ecclesiastical import. It was within this culture that Yale College was founded in 1701, with a mission to educate and train clergy to serve the settler colonialist churches, over 700 of which were in New England by the time of the American Revolution.

Moral Economies and Market Forces

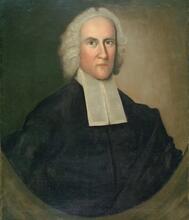

This culture also produced Jonathan Edwards (1703-1758). Born in Connecticut and a Yale graduate (B.A. 1720, M.A. 1723), he was a pastor, revivalist, educator, and missionary, widely considered the most significant early American philosopher and theologian. An inheritor of Puritanism, and of the Reformed tradition from which it stemmed, Edwards embodied many of the continuities and contradictions of that tradition and instigated many of the changes it would undergo. While he was not one of the political “founding fathers” of the United States, he is considered one of its spiritual founding figures who advocated a particular view of society. In our time, when the origin of the United States as a “Christian nation” is a topic of hot debate, it is worth looking at how a formative thinker and historical actor such as Edwards conceived of a proper society, and participated in it. In many ways, as we shall see, the model that Edwards and his contemporaries held was not necessarily appealing to modern assumptions, Christian or otherwise.

In their social theory, the Puritans envisioned a moral economy that was communitarian, emphasizing the interdependence of all citizens, in which individuals subjugated their own interests to promoting the “commonweal,” or common good, with each following their God-given calling and occupying their assigned place in the social structure. Edwards retained this goal of a moral economy, but he came of age in a newly developing market-driven economy, and he strove to preserve the old while scrutinizing the new. Traditional agrarianism, still the backbone of 18th-century New England’s labor force and economy, was giving way to mercantilism, especially in the seaports and river towns, which were becoming more and more connected to the English imperial trade network in the Atlantic basin and beyond. In Edwards, as in many of his contemporaries, a “commonwealth” ethos resided, often uncomfortably, alongside an emerging individualistic, proto-capitalist one, of which he was highly critical. Even so, Edwards and his family, and his fellow provincial gentry, were swept up in the acquisitive process of refinement—the desire for fashionable houses, accessories, clothing, and other imported material products—even while condemning people of lower ranks who tried to live above their station. In this respect, class-conscious Puritan sumptuary attitudes still survived.

A Royalist Theology

In the most simplistic terms, the Puritan conception of the body politic was one in which “superiors” ruled through a social contract in which “inferiors,” or the governed, voluntarily submitted their wills. For the Puritans, democracy was akin to anarchy. Leaders were to rule in righteousness, according to God’s dictates (as interpreted by the clergy), and provide models of piety, while the people were to obey the God-ordained powers that be. In most colonies—including New Haven—only white, male “visible saints” had the privileges of voting and holding office. The family formed the nucleus of the godly society, in which the husband held sway over the wife, children, servants, and enslaved persons.

This communitarian view still pertained in 18th-century New England, though traditional ideas of hierarchy and deference were leavened by claims of the personal rights of Englishmen, including freedom of conscience in the face of authority and freedom to worship according to one’s own lights. Edwards himself advocated the right of conscience—though only to a point. Likewise, his attitudes about gender were a mix, simultaneously backward- and forward-looking, keeping women in traditional subjection while also in some ways empowering them.

Edwards was socially conservative, in favor of economic and social regulation, and monarchical in his approach. He advocated a form of British nationalism common to his contemporaries that strongly supported the monarchy of George I (who ruled from 1714 to 1727) and his successors. With that dynasty was established the “Protestant Interest” in Britain over against threats of a Catholic monarchy, which, the Puritans’ descendants feared, would renew persecution. Edwards’ theology itself was royalist in nature, with its emphasis on sovereignty, portraying God as king and Christ as prince, with subjects arrayed hierarchically and deferentially below them in attitudes of grateful reception of any blessings. Even heaven and hell, for Edwards, were to be arranged with degrees of glory and damnation for their inhabitants—heavenly life, of which the earthly was a reflection, was to be no place of egalitarian bliss.

Privilege Encounters Pluralism

Yet, for Edwards, God’s authority was not thoroughly despotic but also benign, preserving individual choice—and culpability—within a system of limited authority. Edwards read John Locke on government and on toleration, Richard Steele on manners, and libertarian journals such as The Guardian, John Trenchard and Thomas Gordon’s The Independent Whig, and Joseph Addison’s The Freeholder. His was the view of a provincial, with its roots in the region’s Puritanism, but also reflecting new currents of transatlantic Protestant Dissent.

In the early modern period, as Europeans were, on an increasing basis, sending out expeditions around the globe and invading and colonizing other lands, they were coming in contact with different peoples. Europeans, including the English, arranged these racial and cultural others into a providential view of history that privileged themselves and into a traditional hierarchical social structure that assumed lesser and greater races. The English convinced themselves that their Protestantism, their civilization, and their technology gave them a superiority over Native peoples. Eventually, this religious supremacy evolved into racial supremacy and a codification of white dominance. Encounters with Natives became a rationale for control of their lands and their bodies.

The founding of the Company of New England in 1649 had as one of its goals the missionizing of Indigenous peoples. Under figures such as John Eliot, communities were created at which Natives were educated and trained. In a time when the cohesion of Native peoples was severely weakened by disease, loss of land and resources, and violence, such “praying towns” offered a means of survival—though at the price of full inclusion in neither Native nor English societies. However, when many tribes allied under the Wampanoag leader Metacomet and attacked English settlements in 1675, the inhabitants of the praying towns—those who did not flee or fight for the English—were rounded up and left to starve on a barren island in Boston Harbor. While distrust of Natives had always been present among the English, the brutal conflict known as King Philip’s War (1675-78) catalyzed racial prejudices for centuries to come. Despite all their touting of evangelism of Natives as a chief motive of colonization, the Puritans of New England largely failed, and with dreadful results.

Spiritual Presumptions

Edwards perpetuated what Native historian Ned Blackhawk calls “the presumption of the sanctity of spiritual colonization,” in which Europeans equated their exploitation and oppression of Natives and Africans with the will of God. Colonizers such as Edwards assumed that the task of gospelizing Native peoples gave them a right over not only their lands and their bodies, but their souls; religion was put in service of the imperial project. In his approach to missionizing the Mahicans and Mohawks at the Stockbridge, Mass., station during the 1750s, Edwards took it as a given that anglicization and Christianization went hand-in-hand. He was an instrument of the continuing deprivation of Indigenous peoples of their lands, language, religion, and culture, insisting that they learn English (while he himself refused to learn any Native dialects), adapt to European ways, come to the belief and profession of true religion—and submit to its disciplines.

The practice of slavery was part of this worldview. Venerable Puritan ministers in both old and New England enslaved people of color. The first enslaved Africans were infamously unloaded at Jamestown in 1619, but less than two decades later, colonizers of New England also brought enslaved persons with them. By the end of the 17th century, the number of enslaved persons in New England, both Indigenous and African, was beginning to grow, along with—not coincidentally—English affluence. The 18th century saw that number increase many times, the source of labor increasingly being Africans taken illegally and inhumanely from their own countries, many of them brought across the Atlantic in the holds of New England-owned vessels, and sold in seaports from Boston and Newport to New York and Charleston. Even individuals such as Judge Samuel Sewall of Boston, who questioned not only the growing reliance on slave labor but also the legitimacy of slavery itself, abhorred the idea of “miscegenation,” or mixing of the races.

Slavery was justified by most Puritans and Dissenters as a biblically ordained institution. Enslavement, advocates argued, would provide an opportunity to Christianize individuals who might not otherwise be exposed to the gospel. This proved to be a sham, as very few enslavers made any attempt to teach religion to the people they enslaved, or they were interested only in inculcating into the persons they enslaved a gospel of submission and obedience. Puritans and Dissenters claimed that the purpose of religion was the liberation of the sinful self, but that freedom was, and largely remained, elusive and deferred for people of other races and cultures.

A Calamitous Inheritance

And this transgression, like a cancer, only swelled. As the society as a whole profited enormously from slavery and the slave trade, Edwards, quite typical of a growing number of persons in his class, enslaved a series of individuals. He purchased human beings to benefit from their labor and to relieve his wife and older daughters from housework. But he also brought enslaved people of color into his household to set himself off as a member of that elite class that could afford them—a way, in other words, of commanding deference. He, too, saw slavery as a part of the fallen world’s order as laid out in the Bible. At least early in his life, he had no apparent qualms about procuring “servants”—the polite word for enslaved persons—through the slave trade, though later in life he came to oppose the “disfranchising” of free Africans. All the same, debtors, war captives, and the children of enslaved persons were, for Edwards as for many of his peers, legally held in perpetual bondage. Among the tragic inheritances of the Puritans and their descendants are the oppressive inequities they built and perpetuated around race and ethnicity, the dispossession of Indigenous peoples, and the condoning and expansion of enslavement, all in the name of the Christian religion.

Make no mistake: the Puritans and their Dissenting progeny have given us many important legacies, including a Congregational tradition that was and is deeply involved in reform, justice, and equity movements, from abolition to civil rights; a rich history of preaching and spirituality; and an emphasis on education, contributing to a storied and diverse intellectual culture, among other things. But if we try to ascertain the faith of the revolutionary generations beyond an appeal to a vaguely evangelical sort of belief in God and Jesus Christ, or beyond the myth of American chosenness that the Puritans handed down, and look closer at the sort of society that “founding” figures such as Edwards assumed was righteous and correct, we would be more circumspect about the kinds of claims we make about our beginnings as a nation and as a people.

Kenneth P. Minkema is Editor of The Works of Jonathan Edwards at Yale University and Director of The Jonathan Edwards Center, which is housed at YDS.