The Contemplative Life and a NASCAR Epiphany

The term “Christian values” has become notoriously opaque. I find myself cringing when I speak the phrase aloud not just because of what it has sometimes come to represent in popular sound-bite culture with colonialist, racist, and nationalist connotations, but because of what it fails to signify for many (trust, compassion, healing, planetary care, and justice). Thich Nhat Hanh, the revered Vietnamese Zen Buddhist, once described a fellow Zen teacher who was so exasperated by the misrepresentation of his tradition’s founder that he declared, “I am allergic to the word ‘Buddha’ … Every time that I have to utter the word ‘Buddha,’ I have to go to the bathroom and rinse my mouth three times.”[1] I wonder how many Christians have felt the same distaste in witnessing Christianity so distorted in the public square.

If Christian values stand for anything, they must represent an unswerving commitment to care about our interconnected communities, with a hopeful willingness to attend to their pain.

We have been born into a moment whose urgency is beyond our ability to articulate. Searing poverty, bitter polarization, extreme weather, and persistent racism rage on with a sinister complexity that overwhelms our capacity to respond. American church attendance in free fall along with a dozen other apocalyptic catastrophes have left Christians bewildered and overloaded. It’s no wonder that countless recent public conversations have been adorned with myriad references to “trauma,” “self-care,” and “safe space.” These words point to our individual and collective anxiety. Given humanity’s spectacular capacity to face our own ruin with indecision at best and apathy at worst, how might Christian values chart a path forward?

Valuing What Jesus Valued

In moments of overwhelm, I notice in myself an impulse to circle my own wagons, armor up and hunker down. In a world where everyone cannot be safe, the instinct is to try at least to insulate our families and dear ones. It is tempting to create bunkers of self-protection, drawing circles of care in smaller and more manageable diameters. Thankfully, in our wiser moments, we realize that isolation is a physical and metaphysical impossibility, an illusion that only quickens our demise. If everything is connected to everything else, then the armor of self-protection only hastens what we fear. Isolating encourages others to isolate. Cynicism is contagious. The road to hell is not paved with good intentions, but numbness, disconnection, and despair.

If Christian values stand for anything, they must represent an unswerving commitment to care about our interconnected communities, with a hopeful willingness to attend to their pain. In a time of global urgency, a low-tech, if imprecise definition might be helpful: Christian values are simply the things Jesus valued—justice for the poor, radical love of neighbor, repentance, and the invitation to follow Jesus in his self-giving life and death. Seen this way, the Christian life is lived between two incisive questions that YDS professor Miroslav Volf encourages us to ask ourselves with boldness: Do I value the things that Jesus valued? Does Jesus value the things that I value? For most of us, the answers to these questions are more than humbling.

How Did I Get Here?

Several years ago, I found myself preaching in the Rolex Room, an exclusive VIP conference space overlooking NASCAR’s Daytona 500 raceway. As a contemplative teacher, I had been invited to lead a mindfulness workshop at an international gathering of professional athletes and sporting executives: coaches from the NFL, NBA, the International Olympic Committee, and several other prominent athletic federations from across the globe to learn about the latest research in elite athletic performance. “How did a divinity-school-trained lay preacher like me land in this unlikeliest of places?” I wondered.

A few years earlier, I had founded a contemplative community called Copper Beech Institute. We began as a small community that would practice mindfulness, contemplative prayer, and meditation in silence together on Wednesday evenings. Soon we began hosting silent retreats, welcoming contemplative teachers from around the country, and offering an occasional workshop. Our community quickly grew in person and online. After a decade, we were a flourishing community of tens of thousands of practitioners from over 50 countries. Whether we were working with aerospace engineers, superior court judges, Fortune 500 executives, coaches, kindergarten students, or inmates at the county jail, they were surprisingly united in the reasons for seeking out such community.

Hope-Drenched Moment

What bonded together this heterogenous collection of the non-affiliated, spiritually independent, devoutly religious, nones, and dones, whether at Cooper Beech or Daytona Speedway, was a longing to connect with others and a desperation to learn wiser ways to navigate the madness of contemporary life. No matter their background, all sought relief from suffering. For some it was stress, loss, and isolation that brought contemplative prayer and practice into their lives; others sought purpose, ritual, and connection to God and neighbor. Whether desiring to improve performance on game day or seeking relief from the stress of daily life, at the heart of their search was a yearning for what could keep them anchored and hopeful in a dispiriting, fragmented, and aching world.

Often without knowing it, they were longing for the gifts of the Holy Spirit (Galatians 5.22-23) through contemplative practices and/or prayer. In New Seeds of Contemplation, Trappist monk Thomas Merton attempts to define contemplation for modern life.

Contemplation is the highest expression of [our] intellectual and spiritual life. It is that life itself, fully awake, fully active, fully aware that it is alive. It is spiritual wonder. It is spontaneous awe at the sacredness of life, of being. It is a vivid realization of the fact that life and being in us proceed from an invisible, transcendent, and infinitely abundant source. Contemplation is above all, awareness of the reality of that source.[2]

Contemplation, or contemplative prayer, is the opening of mind, heart, and one’s whole being to God; it’s the regular and intentional surrender to the wellspring of hope and freedom. Contemplation is both a relationship initiated by God—whereby one practices being fully present to grace—and the process of transformation arising through the awareness that everything is in God, and God is in all things. (1 John 4:16)

Defying the Overwhelm

Why did Copper Beech Institute grow so rapidly at a time when many traditional communities of faith were struggling to survive? In the years since arriving baffled by my own presence in NASCAR’s Rolex Room and mystified by the many thousands of people who flocked to Copper Beech Institute, I’ve often wrestled with this question. I believe that what people found in our expanding circle of prayer and practice was a community where practical skills, urgently needed to navigate a world increasingly inhospitable to human thriving, could be received, deepened, and shared. These seekers longed to be formed. In a culture drowning in information, people seek transformation; they hunger for a reliable program of self-transcendence where they can discover the spiritual skills necessary to manage lives that feel overwhelming, fragmented, and without purpose.

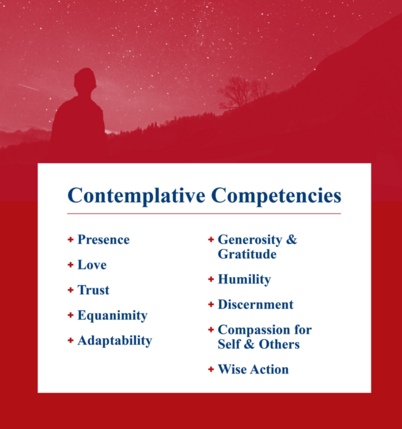

If our only answer to the challenges of our world is to “come to church,” and our church is not teaching the particular embodied skills so many are seeking, then we miss the particular urgent concreteness that communities of faith have within their power to offer. These skills, which I refer to as contemplative competencies, are gifts given through faith, cultivated through contemplative prayer, and deepened through life experience. They are the hopeful embodiment of a life rooted in the Holy Spirit.

In my new role as the Executive Director of Leadership Programs at Berkeley Divinity School at Yale, I frequently reflect upon the question of how hope gets kindled in the lives of believers and through communities of faith. One way is by cultivating these ten contemplative competencies, a constellation of embodied skills informed by the fruits of the Holy Spirit (Gal. 5.22-23).

Copyright © 2023 by Brandon Nappi. Design by Melanie Post

Too often the church has forgotten to teach people how to pray and has lost touch with its contemplative riches. As skills to be cultivated and gifts to be received through grace, these competencies can be a powerful way to renew the church and reframe the conversation around Christian values. To the extent that the church is recognized as a reliable wellspring of wisdom with deep experience in teaching these competencies, it will regenerate itself. Communities of faith will grow as they teach tangible skills born of faith that meet the longings, losses, and injustices of our contemporary condition. To the extent that these competencies are obscured, not taught, or taught poorly, the church will wither. Whether drawing from lectio divina, centering prayer, Ignatian exercises, the rosary, praying the daily office, spiritual direction, or mindfulness (just to name a few), these practices support the cultivation and proliferation of values rooted in the life of Jesus.

Changing Change

To be clear, contemplative prayer and practices alone will not save the church or cause the world to suddenly value what Jesus valued. If the church is to lead a revolution of moral transformation and reform, the church itself must change. Of course, it’s nothing new to say Christianity must change. Christian leaders have been voicing the call to change since the birth of the church. It’s not just that the church must change; it’s that the way we change must change. As a sacred training in change, contemplative prayer and practice offer a hope-drenched encounter with the transforming presence of God that continually realigns us with the one we follow. The fruit of Christian contemplative prayer is simply a life that values ever more deeply what Jesus valued.

One doesn’t need to wait for a stunning mystical experience to realize what Merton discovered one day in the shopping district on the corner of Fourth and Walnut in Louisville, Ky., in 1958—that “I loved all these people, that they were mine and I theirs, that we could not be alien to one another even though we were total strangers.”[3] Only when this kind of love is radiantly reflected in our lives and what we care about, will our values ever be recognized and celebrated as “Christian.”

Brandon Nappi is Lecturer in Homiletics at YDS and the Executive Director of Leadership Programs at Berkeley Divinity School. He is the founder of Copper Beech Institute, a worldwide spiritual community of 50,000 people from more than 50 countries dedicated to sharing contemplative practice. A graduate of the University of Notre Dame, he also holds a doctor of ministry degree in homiletics from Aquinas Institute of Theology.

[1] Thich Nhat Hanh, “Thich Nhat Hanh on God,” Plum Village App, March 25, 2021.

[2] Thomas Merton, New Seeds of Contemplation (New Directions, 1972), p. 1.

[3] A Thomas Merton Reader, edited by Thomas P. McDonnell (New York, 1989), p. 345.