Preaching, Plagiarism, and AI

At the death of King Henry VIII in 1547, the Church of England found itself with a homiletical crisis. Despite severing the links with the papacy, Henry was a liturgical conservative who had allowed only minor changes in public worship. When his young son Edward ascended the throne, the boy king’s advisers were more thoroughly Reformed in attitude, and began the processes that would create a Protestant church in theology and liturgy too.

The emphasis we have come to place on the preacher and their performance as a proxy for the presence of God has exposed our theologies of preaching as often foregrounding performance or technique rather than truth.

The homiletical problem was that not all the clergy had any capacity, and perhaps not much inclination, to preach the pure Reformed faith. They had been raised up as efficient practitioners of the Latin mass, and the work of preaching had been seen as a quite separate and much more specialized kind of activity, not always integrated into worship as is now assumed.

Later in that year Thomas Cranmer, the Archbishop of Canterbury, published a Book of Homilies, appointed to be read at services where no sermon was given—an acknowledgment that quite a few clergy did not have powers equal to the task. Cranmer was also in the process of creating a new liturgy—the first Book of Common Prayer—which from 1549 would require the use of a sermon whenever the Holy Communion service was to be celebrated.

Preaching Texts Not Their Own

It was thus seen not only as acceptable but normal, and sometimes necessary, for preachers to use texts that were not their own. Even when Edward’s short reign ended and Roman Catholicism was restored for some years under his sister Mary I, the new hierarchy published its own sets of homilies to set people as straight as they could manage.

Whether these authorized published versions were used, or congregants were fortunate to have educated clerics capable of producing their own sermons, content was the sole arbiter of appropriateness. Originality was at best an extra, at worst a risk that could lead to heresy. What was valued was not the preacher’s own genius, but an authoritative intelligence that was more institutional than personal.

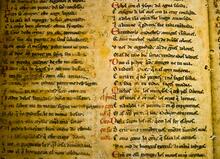

This is hardly the only example from the history of preaching to suggest content could readily come from somewhere other than the mind of the preacher. Much earlier, Caesarius of Arles (d. 542) became one of the most popular preachers of his day by borrowing older sermons freely, especially from Augustine of Hippo (d. 430). There was no attribution in these cases, nor was there scandal; the issue was the quality and orthodoxy of the homiletic product, not the source.

Whatever Happened to Heresy?

Fast forward to the twenty-first century and it seems the greatest sin that could be committed in the Anglican (or other) pulpit is not heresy but plagiarism. This is literally true in the Episcopal Church, where in recent years there have been a number of published disciplinary cases of homiletic plagiarism, but none of heresy—which I cautiously suggest may not actually have disappeared from contemporary preaching.

If anything, the plagiarism issue generates more interest and concern in evangelical circles, where some very prominent cases, even involving a president of the Southern Baptist Convention, reflect the significance of preaching in such settings. As is the case in the mainline churches, however, the soul-searching and outrage do not usually extend to considering why the issue raises hackles in the first place.

Misrepresentation or dishonesty is not trivial, given the expectation of personal integrity in those who hold pastoral office, but it is hard to avoid the conclusion that such congregational or collegial outrage is about something else. The grumbling would be more subdued but not absent, should the modern pastor openly read from some contemporary equivalent of the Edwardian Homilies rather than write something of their own.

Truth or Originality

While these complaints have overtones of consumer dissatisfaction, a sense that the employment transaction is not being honored, even more fundamental is the value placed on originality itself, and hence on personality. While there have long been celebrity preachers, there is something different about a situation where personal and original effort—rather than truth—is deemed to be the touchstone of homiletic substance. Personality has become our “orthodoxy” in liberal and conservative circles alike, and homiletic originality is its sacramental and spoken seal.

These forms of plagiarism owe much to technology, including the printed book. While volumes of sermons have been published (and re-preached) since Augustine’s time, modern preachers have been more likely to have volumes by such as Charles Spurgeon (1834-92) on their shelves. Spurgeon, whose London Tabernacle was the most famous pulpit of its day, did much to promote the idea that the sermon had to be the result of an encounter between the preacher and the Holy Spirit, even while running a handy side business publishing thousands of printed sermons likely to have been repeated without such spiritual experience. Although Spurgeon himself also seems to have been capable of reusing his own sermons and those of others, the arrival of mass literacy and cheap books coincided neatly with the rise of a belief that the Spirit’s work was largely within the individual, and the results of this shift of authority from Church to individual experience are still with us.

A New Ghost in the Machine

The recent famous cases of plagiarism of course involved the internet, which greatly expands the range of material that may offer the jaded homilist temptation, inspiration, or consolation. Now into this already crowded set of offerings comes the prospect of Artificial Intelligence.

While the well-known platforms like ChatGPT and DeepAI already produce outlines and even whole sermons better (at least on paper) than those some (but not all) of you heard last week, there are also dedicated sites like “sermonoutline.ai” whose products are more bespoke, and which seek to assuage the anxiety of the prospective user, on the one hand by urging the continuing significance of personal study (without quite saying why), and on the other by pointing out that this original material does not require any sort of disclosure. They do not however mention doctrine, or God.

AI does not yet write really excellent sermons or top-class essays, but it isn’t far off, and imagining it won’t get there would be foolish. Its technical capacity will soon exceed that of most writers, and in time presumably AI simulants will look and sound as convincing as the human preacher. In this case we face yet another version of the challenge common to Church and politics of confusing edification and entertainment, to our deep peril.

Performance Anxiety

Not every use of AI will be at this extreme, though. If a preacher were to provide prompts to AI, a set of points they wanted to make, and then edited the result, the sermon might actually be better as well as easier to produce. Will it however be true? Here as otherwise with AI, the huge threat and significant potential is as much about ourselves and our choices as about the technology itself.

How will the anxious detectors of plagiarism cope? Concern for originality in itself constitutes a weak objection to AI homiletics. The predicament we find ourselves approaching is not caused by AI but revealed by it. The emphasis we have come to place on the preacher and their performance as a proxy for the presence of God has exposed our theologies of preaching as often foregrounding performance or technique rather than truth.

“Through Whom All Things were Made”

AI is good at doing some things, including producing texts with polished rhetoric, that might not really have been as important as we thought they were. Yet AI is neither divine nor human. It can neither love nor suffer, neither save nor bless. Like a book, it can reveal wisdom or conceal deception; it cannot however tell us what is true. Yet it will probably claim to do so, considering some of the examples that have already made themselves known, precisely because it cannot tell the difference, either between its work and truth, or between itself and God. In that failure it may condemn itself, but we will bear the consequences.

Given the fragmentation of Church and for that matter of western society, we will of course see varied responses. AI will be at the center of new forms of sophistry and spectacle purporting to be preaching or even Church; but in other places, perhaps people might become more relaxed about hearing something by Augustine or Hildegard or Spurgeon or Sojourner Truth, as well as listening to preachers who have wrestled with the text of scripture and shared the original result, not because their own words need to be heard, or because they were grandiloquent, or were repositories of personal spiritual knowledge, but because they were believers who trust in the essential intelligence, the Word, through whom all things were made.

The Very Rev. Andrew McGowan is Dean and President of Berkeley Divinity School, the Episcopal seminary affiliated with YDS. He is also McFaddin Professor of Anglican Studies and Pastoral Theology at YDS. An Anglican priest and historian, his scholarly work focuses on the life of early Christian communities and on aspects of contemporary Anglicanism. His books include Ascetic Eucharists: Food and Drink in Early Christian Ritual Meals (Oxford, 1999), Ancient Christian Worship (Baker Academic, 2014) and Seven Last Words: Creation and Cross (Cascade, 2021). His blog on the Revised Common Lectionary and other issues can be found here.